The CQRS pattern can do wonders: it can maximize scalability, performance, security, and even “beat” the CAP theorem. Nonetheless, CQRS has acquired a controversial name because of the complexity it introduces. For instance, in his article on CQRS, Martin Fowler argues that the pattern should be applied sparingly and even cautiously:

- “… for most systems CQRS adds risky complexity”

- “… you should be very cautious about using CQRS”

- “So while CQRS is a pattern that’s good to have in the toolbox, beware that it is difficult to use well and you can easily chop off important bits if you mishandle it.”

From my point of view, the CQRS-induced complexity is largely accidental, and thus can be avoided. To illustrate my point, I want to discuss the goal of CQRS, and then analyze 3 common sources of accidental complexity in CQRS-based systems.

The Goal of CQRS

The goal of CQRS is to enable representation of the same data using multiple models. Not scalability, not availability, not security, not performance. Same data in multiple models. That’s it. The rest is byproducts. Don’t believe me? Listen to Greg Young’s talk at the DDDEU2016 conference, where he says that CQRS was invented to support implementation of Event Sourcing. And, as you probably know, the Event Sourcing model is awesome for writing data, but terrible for reading. That’s why he needed CQRS back then: to represent the same data in multiple models.

How does CQRS achieve this goal? By making sure that only one model serves as the source of truth, and all changes are committed to this model only.

Let’s see how this understanding can help us tackle some complexities.

Complexity Trap #1: One-Way Commands, or Overzealous Segregation

All definitions of CQRS that I’m aware of follow this pattern:

- CQRS is based on the CQS principle, which states that operations should be divided into two groups: commands that change data, and queries that return data. Once we elevate this principle to the architectural level, we get a system with use cases segregated into same two groups: commands and queries. Each use case can be either command or query, but never both.

- Once the use cases are segregated, we get quite a few benefits: multiple models, different persistence mechanisms, independent scalability, etc.

Do you sense something wrong here? The issue is subtle: all definitions of CQRS usually start with the solution — the segregation, and only afterwards define the problem — multiple models. This causes too much zeal about the segregation: going as far as to define commands as one-way, where you get Ack/Nack response from the server, but have to poll some read model store for the actual command execution result. In other words, complexity hell unleashed.

Solution: Relax the Segregation

Let’s take a step back and reconsider the segregation. We’ve seen that, according to CQRS, to represent the same data in multiple models, a use case can either write or read data. It’s a no-brainer that a read model shouldn’t update anything, since otherwise we’d end up with multiple sources of truth. But should you really keep your commands void?

Not really. Without violating any principles, a command can safely return the following data:

- Execution result - success / failure;

- Error messages or validation errors, in case of a failure;

- The aggregate’s new version number, in case of success;

This information will dramatically improve the user experience of your system, because:

- you don’t have to poll an external source for command execution result, you have it right away. It becomes trivial to validate commands, and to return error messages; and

- if you want to refresh the displayed data, you can use the aggregate’s new version to determine whether the view model reflects the executed command or not. No more displaying stale data.

Speaking of data, can we relax the segregation a bit more? In many cases, any data contained inside the affected aggregate can be returned as part of the command execution result. However, there is a slight nuance here: make sure that the returned data can be queried later on from one of the read models. Otherwise there is a slight risk that the data might be lost, in case the response doesn’t make its way to the client.

You can see an example of such approach in Daniel Whittaker’s blog, where he discusses the usage of command execution objects for validation of commands.

Also, in this gist you can see the command execution result object that I use in C#.

Complexity Trap #2: Event sourcing

For historical reasons, CQRS is closely associated with the Event Sourcing pattern. After all, CQRS was invented to make Event Sourcing possible. But let’s reevaluate the coupling between the two patterns.

As I’ve said before, the goal of CQRS is to allow representation of the same data in different models. If you’re working with an Event Sourced Domain Model, you absolutely need CQRS to be able to execute queries. However, there are lots of other perfectly valid reasons to implement CQRS that are not related to Event Sourcing:

- Your system should display its entities in different representation models.

- You have to support different querying models (search, graph, documents, etc.).

- The difference between writes and reads differs greatly, and you want to scale them independently.

- You hate O/RMs.

Does this mean that in all these cases you have to go down the Event Sourcing route? If you do, you’re deep in a complexity trap. Event Sourcing is a way of modeling business domains. Not just a way, but probably the most complex way. Therefore, you should employ Event Sourcing if, and only if, your business domain justifies it. Let’s see how you can implement CQRS in other cases.

Solution: CQRS != Event Sourcing

We’ve been taught to generate projections by writing handlers for events. But how do you implement projections without events? There is another way to do projections, and I call it “State Based Projections”. This topic merits a post of its own, but I’ll briefly describe three ways to implement “State Based Projections”:

1. “Is Dirty” Flag

You can mark an entity that was updated by raising the IsDirty flag, and implement a projection engine that will query for dirty instances and project the updated data into distinct models. To rebuild projections, you just have to raise the flag back for all records.

2. Catch-Up

In relational databases, you can track commits at the table level. For example, in SQL Server you have a built-in mechanism for that, the “rowversion” column. Such functionality can be implemented for other relational databases as well. A projection engine will query updated rows in a catch-up-subscription-like way, and project the updated data. To rebuild a projection from scratch, you have to “rollback” the last known commit id back to 0.

3. Database Views

If you use a relational database, and all you need is to represent its data in different models, database views will work great. Yep, a perfectly valid CQRS system can be implemented in the database. Probably the least sexiest solution - but not only does it work, it also naturally follows the CQRS pattern.

These ways to project models may not be cool and sexy, but they work. I’ve seen quite a few projects that have employed them, and they worked like a charm, without unjustifiably drowning in Event Sourcing related complexity.

Wait, did I just suggest to ignore Event Sourcing at all costs because it is complex? Hell no! Event Sourcing is one of the most important tools in your toolbox. But as any tool, use it in its context - business domains that bring business value: Core Subdomains. On the other hand, Generic and Supporting subdomains, that are simple enough to be implemented with Transaction Script or Active Record patterns, can still benefit from CQRS. In such case, employ the simplest tool that will do the job, and rip the benefits of CQRS using State Based Projections.

Complexity Trap #3: Too Much of a Good Thing

The Microservices hype has attracted lots of attention to CQRS: if you have a set of independent services that need to query each other’s data, CQRS is the common solution. However, I’ve seen this approach produce monstrous data flow diagrams of services projecting lots of data between them.

This is not always bad, but in many cases it might be a signal to take step back and reconsider your decomposition strategy. Chances are that your services are too fine-grained and do not reflect the business domain’s boundaries. If this is the case, you can greatly reduce your architecture’s complexity by realigning services boundaries with their corresponding business domains.

CQRS: Decomplexified

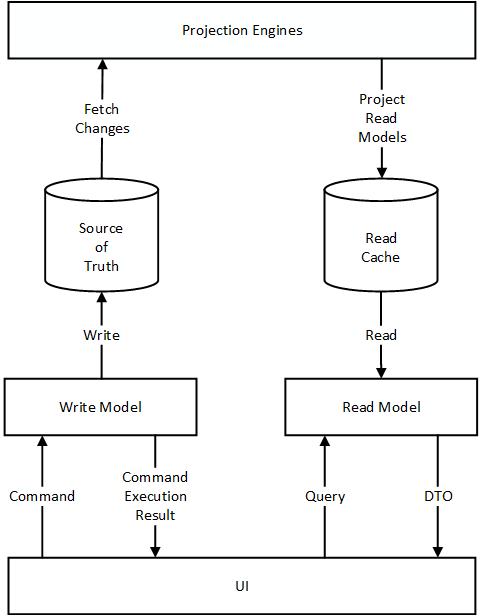

I want to sum it all up with a diagram of CQRS:

This diagram differs from other diagrams you can find on the web:

This is the CQRS pattern the way I both see and implement it. Commands have responses. The projection mechanism defined is abstractly without any implementation details. Inside it may be based on events, or on state, or even a database view. And finally, there is no glimpse of Event Sourcing. Model the system’s business logic as required by the business domain: Active Record, Domain Model, or Event Sourced Domain Model.

As with every correctly applied tool, CQRS should reduce complexity, not induce it. If your architecture’s complexity grows, you’re doing something wrong.